The Conundrum of Sanitation

In 2022, over 1.7 billion people still do not have basic sanitation services. The World Health Organisation (WHO) further reports that of this 1.7 billion, 494 million defecate in open spaces.

Numbers are useful. But let's add some context to these statistics.

Sanitation has historically been an after-thought to development, which is reflected in the use of non-specific and non-contextual sanitation policy. The reliance upon a global, standardised monitoring programme is ineffective in achieving acceptable sanitation access. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme defines households as having improved sanitation when they ‘use a facility that is not shared with other households’, and is either: a flush toilet, a ventilated improved pit latrine, a composting toilet, or a pit latrine with a slab. It is important to note that ‘improved’ in no means equals safe, and the WHO itself recognises this constraint upon the term. What counts as safe is highly differentiated between the rural and the urban. Whilst a pit latrine may be a form of safe sanitation for a rural village, it is not safe for a dense settlement, nor areas with flooding or dug wells for drinking water. It becomes essential that sanitation policy becomes highly contextual. We must desire to utilise local knowledge, and deviate from the idea of a blanket strategy.

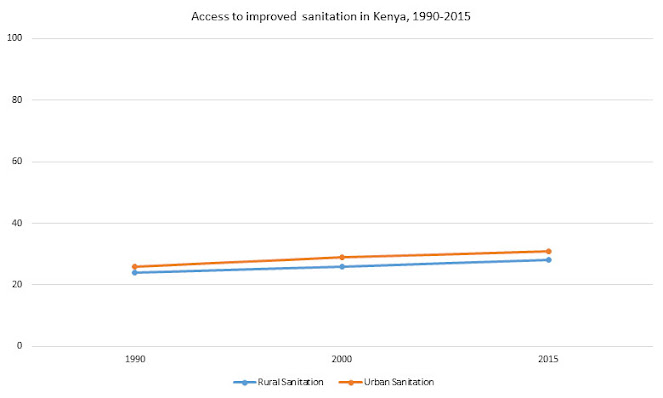

Figure 1.

Progress is slow. Changes in access to improved sanitation in Kenya between 1990 and 2015.

If we look to Nairobi, the rapid urbanisation of the city has huge consequences for sanitation, with ever-growing informal settlements materialising around the city. Only 40% of Nairobi is connected to the sewerage system. Notably, the World Bank has significant involvement in the implementation of sanitation strategies in Nairobi. Investing in actors like Nairobi City Water and Sewerage Company (NCWSC) and the Kenya Informal Settlements Improvement Project (KISIP), the World Bank seeks to enhance the government’s national development plan for sanitation. However, more deeply, we must understand the role of individual political and economic power in dictating who benefits from government provision. National policies rarely extend their influence to the informal settlements within Nairobi, due to a number of factors, but including access issues like narrow and poorly maintained roads. Informal settlements thus must rely upon decentralised forms of service provision, where there is no guarantee of consistent provision, nor a regulation of quality. Here, the issue of sanitation in Nairobi becomes a matter of class and income, where the wealthy residents of the city are privileged with safe, regulated sanitation, and the poor are not.

This distinction has an unwelcome familiarity to that of the colonial era. The sewerage system in Nairobi was developed during colonial rule to serve the elite, and mostly white, population of the city. Sanitation thus became a divisive tool in which those left without services were forced to innovate their own means of water supply and sanitation. Since the colonial era, there has been a continued systematic failure of the city to escape its infrastructural colonial legacies, and consequently, sanitation provision has not been equalised. Whilst now the white population of Kenya has significantly fallen, the dominating dynamic of inequality has now transformed to one of wealth, rather than race. Today, wealth inequalities mimic the racial inequalities seen during colonial rule, where access to sanitation is representative of wider issues of power and agency.

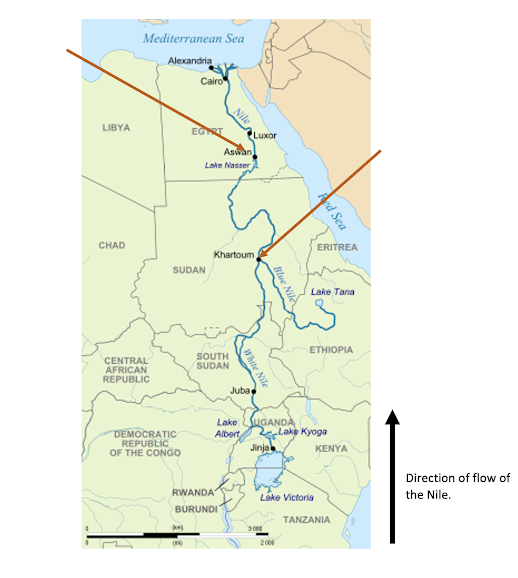

Figure 2.

The PeePoo bag.

Though, concluding this post, if we move beyond the global development agenda towards the ways in which local residents and grassroots organisations seek to contest the inadequate sanitation provisions, we can see an abundance of opportunity created within their communities. If we look at an impact assessment report of the ‘Peepoo bag’ conducted by T.H.M. Ondieki and M. Mbegera (2009), we begin to understand the ways in which an interdisciplinary and bottom-up approach is essential in meeting the sanitation needs of communities. The Peepoo bag is a ‘self-sanitising biodegradable personal single-use toilet’, and is particularly suitable for informal settlements or dense areas with a lack of space for other sanitation methods. The strategy considers the local context that it seeks to aid, and it therefore contains urea, which sanitises the human waste from all dangerous bacteria, viruses and parasites, allowing it to be stored in homes for up to 24hours. The bag enables its users to not be hindered in their daily activities by their sanitation needs, where other strategies may require individuals to walk long distances, or join long queues, to use shared toilets. Instead, like for many others, sanitation becomes just a part of life, rather than something that dictates their existence.

Comments

Post a Comment