The Transboundary Effects of Water

Source: Wikipedia [adapted].

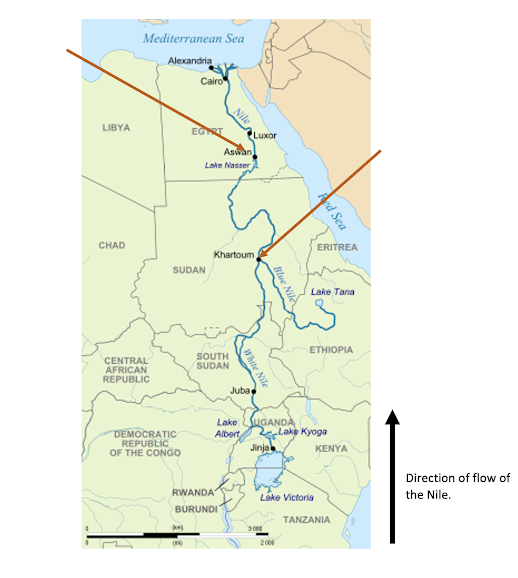

The Aswan High Dam

(in Aswan)

Since the planning of the dam in 1952, and its completed construction in 1970, the dam has been the topic of much technical, political and social debate. The dam, costing $1 billion, was constructed with the intention of providing the long term storage of water to meet agricultural demands, generating electricity, guaranteeing water supply and protecting Egyptian land from floods. Yet, if we analyse the construction of the dam beyond its immediate benefits to Egypt, we can start to uncover the socio-economic repercussions of such an infrastructural project. A notable consequence of the construction of the dam was a loss in the fishing industry. Sardinella (sardine) catches fell by 80% between 1960 and 1970, impacting fish stocks in both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. One research team found a decrease, after 1966, in the relative abundance of almost all species in the Mediterranean Sea, and whilst these species later made a resurgence, during this time there were some important further implications, particularly with a loss of livelihood for fishing communities. Here, we must consider a form of politics of representation, with fishing communities unable to assert comparable agency in protecting their livelihoods, whilst powerful actors reaped benefits from the dam. Within a transboundary basin which lacks an institutional framework to promote the cooperative use of resources, there is significant scope for conflict to arise. And, in the pursuit of national gain, the construction of the Aswan High Dam created a multitude of negative externalities for various groups across and around Africa. However, with much attention paid to the failures of the dam, it is clear that this infrastructural project became a pivotal point in highlighting the importance of viewing the Nile through a transboundary lens.

The Grand Renaissance Dam (GERD)

(in Khartoum)

GERD, an almost finished 6450MW hydropower infrastructural project in Ethiopia, is another significant example of anthropogenic interference with the flow of the Nile. Ali and Admasu (2021), from the University of Ethiopia, write about GERD from an Ethiopian perspective:

'Historically, the Nile basin has been dominated by unilateralism, exclusion, colonial and neo-colonial drives to justify Egypt's and Sudan's monopoly.'

Figure 2.

More about GERD, from the Ethiopian position.

The water of the Nile possesses the capacity to spotlight a continental power struggle. Here, we can observe feelings of hostility, and concerns of power, in the dynamics of usage of the Nile. As such, Ethiopia perceives the dam to be an act of rebalancing access to the Nile, countering the privileges, of colonial origin, of the downstream nations. On the other hand, Egypt argues its 1929 and 1959 colonial-era agreements protect its use of the Nile. Furthermore, they argue that the dam's construction will have catastrophic effects, for example, with a loss of forests and wildlife habitats, and negative impacts upon agriculture. Although, we must question the extent to which colonial-era agreements should stand. Privileging African voices and valuing the agency of African countries to govern themselves, it is surely important to remove any remaining significance of the colonial contribution to the debate. However, at this time, scholars theorise that the solution to this conflict is multidisciplinary cooperation (see Figure 3), where river riparians must be willing to enable each other to invest and grow, and thus become less dependent on the river's resources. For example, one article suggests that Egypt trades its knowledge of agriculture for increased water rights, thus ensuring a more equitable distribution of power. In this example, GERD is a transboundary issue, representing a culmination of debates over water, post-colonialism, and development.

Figure 3.

Calls for transboundary cooperation in the management of Africa’s water issues.

From these two examples, we have seen the capacity of the Nile to dictate transboundary politics in Africa. Water is one of the world's most precious resources, and the challenges we see around the Nile repeatedly prove it.

Comments

Post a Comment