The Silenced Voices of COP

COP: The United Nations Climate Conference.

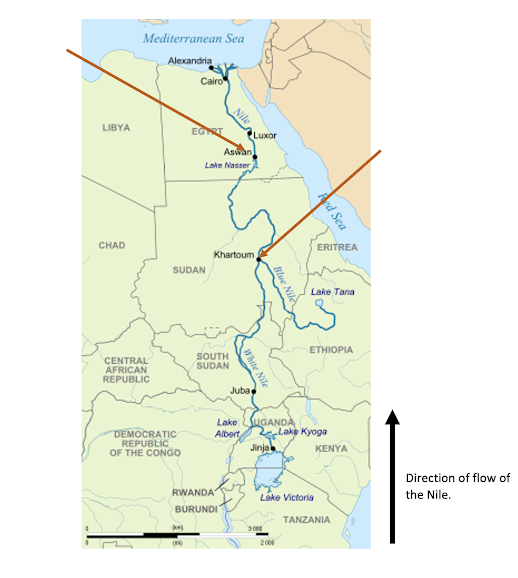

Figure 1.

I recently came across an interesting article from Greenpeace, which framed the recent events of COP27 in a way I’d not seen before. Titled: ‘COP27 stifles dissent, ignores impacted voices & puts polluters before climate justice’, the article summarises deep flaws within the COP27 negotiation process. This was interesting to me. I had heard much discourse of the event over the past few months: amongst my peers, from my lecturers, on the news. The world’s annual COP seems to represent the pinnacle of progress, hope and inclusivity. On the surface, common media discourse represents discussions and negotiations as a fair and democratic process, with all actors working towards a united goal: to save our planet. Reflecting now, I somewhat think I was consumed by the westernised perspective and narratives. For most of the West, yes, COP is a place of cooperation and national gain. I can now understand that this is not the experience of all actors.

The politics of representation. An idea that summarises questions of who is represented in the public sphere, and how ‘modes of depiction are inherently powerful and political’. Matters of representation are highly contested, and push us to ask questions of representation in all of our own personal interactions, alongside the interactions we observe and hear of. What is the right way to do representation? Is there a right way? Can we achieve equal representation? What would equal representation look like?

Figure 2.

Africa denoted as the ‘world’s most vulnerable communities’ in AWARe’s launch.

With water as the central focus of this blog, it becomes interesting to analyse issues of water and representation as interconnected at COP27. The President of the UN General Assembly, Csaba Kőrösi, stated “This is the water COP”, thus, if we take a closer look at one initiative launched at COP27, The Action for Water Adaptation and Resilience (AWARe) (see Figure 2), it appears that global cooperation at improving water security, adaptation and sanitation is a key focus. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) theorises that this initiative will drive cooperation that addresses water resilience and adaptation, focusing first on the world’s ‘most vulnerable people’, for which they have decided is the African region. Furthermore, a ‘delivering action’ of the AWARe initiative is ‘trainings, technology transfer, knowledge exchange, roundtables and outreach activities.’ Whilst the direction of these transfers is not specified, it can be somewhat assumed that the likelihood is a transfer of westernised knowledge and technology towards countries within Africa. Like in most narrations of global interactions, here the African continent has been depicted as in need of saving, with us, the west as the saviours.

This unequal relationship can also be observed within the direct interactions at the COP27.

Whilst also being designated the water COP, others have stated that this COP was ‘supposed to be the Africa COP’. An opportunity for the usually unheard voices to have a platform, an opportunity for the continent to represent themselves in decision making, rather than have a western actor decide for them. Disappointingly, again thinking through the idea of the politics of representation, power dictated discussions, with the microphone often being handed to the polluters. Similarly, reflecting on COP26, the Covenant of Mayors in Sub-Saharan Africa (CoM SSA) concluded that despite many believing that Africa’s participation in negotiations was essential to a successful COP, Africa was ‘not only underrepresented at COP26, but the continent’s priorities are not fully represented in the final agreement’. Hence, COP26 has since been criticised as the most exclusionary climate summit, ever.

Figure 3.

These criticisms can be observed within the realm of water. One of the four key goals of COP26, ‘secure global net zero as soon as possible and keep 1.5 degrees within reach’, involves the protection of degrading water sources. For the city of Cape Town, this then involves questions of governance and power. Outwardly, municipal and national governance should have the capacity to protect water sources. Yet when we look at the 2018 water crisis in Cape Town, multinational corporations, the same ones who are handed the microphone at every COP, seem to have ultimate authority. When officials asked for a 45% reduction in commercial water use, Coca-Cola refused to amend its 44million litre monthly withdrawals, and thus, Cape Town sought other ways to decrease water usage. Ultimately, this exemplifies the issue at heart here. The voices of Africa are clouded by power. The polluters have the microphone, and no incentive to change behaviour. The West claim to prioritise African voices, but their words and actions at international summits seem to suggest otherwise.

Comments

Post a Comment